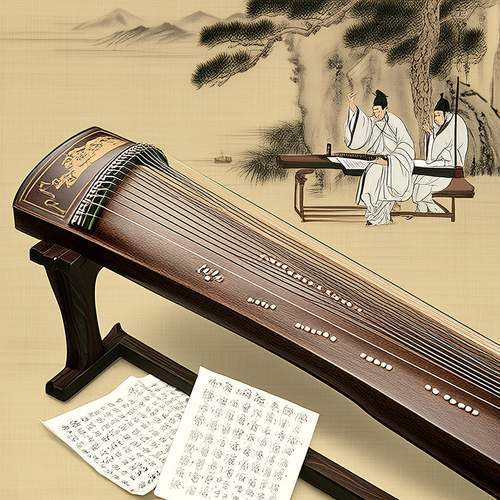

The ancient Chinese guqin, a seven-stringed zither, holds a revered place in the cultural and musical history of China. Among its many unique features, the guqin's notation system—known as jianzipu or "simplified character notation"—stands out as a fascinating blend of calligraphy, music, and philosophy. Unlike Western musical notation, which relies on staff lines and note symbols, jianzipu employs a complex system of abbreviated Chinese characters to convey not only pitch and rhythm but also the nuanced techniques required to play the instrument. This system has preserved the guqin's repertoire for centuries, offering a window into the artistic and intellectual world of ancient China.

The origins of jianzipu can be traced back to the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), though it reached its mature form during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The notation is a radical departure from earlier methods, such as wenzipu , which used lengthy prose descriptions to indicate finger placements and strokes. Jianzipu, by contrast, condenses these instructions into a single composite character, often combining elements that denote the left-hand position, right-hand technique, and string to be played. For example, the character for "da" (打) might be modified to indicate a specific plucking motion, while another component could specify the string number. This compact yet intricate system allows skilled players to interpret centuries-old scores with remarkable precision.

What makes jianzipu particularly remarkable is its inseparable connection to Chinese written language and cosmology. Each symbol is not merely a technical directive but a visual and conceptual artifact. The characters often incorporate strokes that evoke the movement they describe—a downward brush might mirror the motion of a finger sliding along a string. This synesthetic quality reflects the guqin's status as an instrument of the literati, played not for public performance but for personal cultivation and communion with nature. The notation thus becomes a meditative practice in itself, requiring the player to engage deeply with both the music and the cultural ethos it embodies.

Despite its elegance, jianzipu presents significant challenges to modern musicians and scholars. The notation lacks explicit indications of rhythm or tempo, relying instead on oral tradition and the interpreter's understanding of stylistic conventions. This ambiguity has led to varied interpretations of the same piece, with contemporary players often debating the "correct" phrasing or emphasis. Some modern guqin practitioners have attempted to transcribe jianzipu into Western staff notation, but such efforts inevitably lose the tactile and visual poetry of the original. The very imprecision of the system—seen by some as a limitation—is arguably its greatest strength, allowing each generation to reinvent the music while maintaining a tangible link to the past.

In recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in jianzipu, fueled by global fascination with traditional Chinese arts and UNESCO's 2003 designation of the guqin as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Academic institutions and guqin societies worldwide now offer workshops on deciphering the notation, while digital projects aim to catalog and analyze surviving manuscripts. Yet, for all these efforts, jianzipu remains an esoteric art, accessible only to those willing to dedicate years to its study. This exclusivity mirrors the guqin's historical role as an instrument of the elite, yet it also ensures that those who master its language become custodians of a living tradition.

The endurance of jianzipu speaks to its profound adaptability. While firmly rooted in pre-modern Chinese thought, it has proven capable of accommodating contemporary innovations—some avant-garde composers now write new works in the ancient script, pushing the boundaries of guqin expression. At the same time, calligraphers and visual artists draw inspiration from the notation's aesthetic, creating works that blur the line between music and graphic art. In an age of digital standardization, jianzipu stands as a testament to the enduring power of analog systems to convey complexity, beauty, and human touch.

To encounter jianzipu is to engage with a living palimpsest of Chinese history. Each mark on the page carries the weight of centuries, yet remains open to reinterpretation. The notation demands not just technical skill but a willingness to inhabit the mindset of the scholars and monks who once played these melodies in mountain retreats or imperial courts. In this sense, learning jianzipu becomes an act of cultural time travel—one that continues to resonate in the 21st century, as musicians across the world discover the guqin's timeless voice.

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025