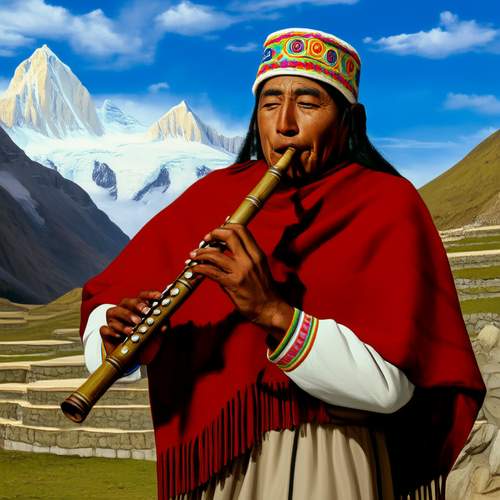

The haunting, breathy tones of the quena flute have echoed through the Andes for centuries, carrying with them the soul of Peruvian musical tradition. Unlike many other wind instruments, the quena’s distinct sound—simultaneously melancholic and uplifting—has made it an enduring symbol of indigenous Andean culture. Carved from bamboo or wood, this notched flute predates the Inca Empire, with archaeological evidence suggesting its use in ancient rituals and communal celebrations. Today, the quena remains a vital part of both traditional and contemporary Peruvian music, bridging the gap between ancestral heritage and modern expression.

To understand the quena’s significance, one must first appreciate its physical simplicity and acoustic complexity. Typically measuring between 25 to 50 centimeters in length, the instrument features six finger holes and a thumb hole, allowing for a range of approximately two octaves. What sets it apart is the U-shaped notch at the blowing end, which requires the player to direct their breath at a precise angle to produce sound. This technique, known as edge-blowing, demands control and subtlety, often taking years to master. The quena’s timbre—airy yet resonant—can mimic the whispers of wind through mountain passes or the cries of birds native to the highlands.

The historical roots of the quena run deep, with traces of its existence found in the artifacts of pre-Columbian civilizations like the Nazca, Moche, and Wari. For these cultures, the flute was far more than a musical tool; it was a sacred object believed to mediate between the human and spiritual realms. Inca legends speak of the quena’s power to summon rain or communicate with deities, and its music often accompanied rites of passage, agricultural cycles, and even battles. Spanish colonization in the 16th century suppressed many indigenous traditions, but the quena survived, adapting to new contexts while retaining its ancestral essence.

In contemporary Peru, the quena has transcended its ceremonial origins to become a versatile instrument in genres ranging from folkloric huayno to urban chicha and even jazz. Musicians like Jean Pierre Magnet and Manuelcha Prado have elevated its profile, blending traditional techniques with modern innovations. Meanwhile, festivals such as the Fiesta de la Candelaria in Puno showcase the quena’s centrality to communal identity, where hundreds of players gather in synchronized performances. The instrument’s adaptability has also made it a favorite among global audiences, with Andean fusion bands introducing its sound to international stages.

Despite its enduring popularity, the quena faces challenges in the 21st century. Mass-produced plastic versions threaten the artisanal craft of hand-carved bamboo flutes, while younger generations often gravitate toward electronic music over traditional forms. Yet, grassroots initiatives led by master craftsmen and educators aim to preserve the quena’s legacy. Workshops in Cusco and Lima teach not only playing techniques but also the cultural narratives embedded in each note. As a testament to its resilience, the quena continues to inspire—whether in the hands of a Quechua elder or a Tokyo-based experimental musician—proving that some voices, once heard, are impossible to silence.

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025