Japanese Gagaku, the ancient imperial court music and dance, stands as one of the world's oldest continuously performed musical traditions. With roots stretching back over a millennium, this art form embodies the elegance and solemnity of Japan's aristocratic past. Unlike many other traditional music styles that evolved through folk practices, Gagaku was meticulously preserved within the imperial household and major shrines, allowing it to survive nearly unchanged through centuries of political and social upheaval.

The term Gagaku translates literally as "elegant music," and its repertoire consists of three primary categories: Kangen (instrumental ensembles), Bugaku (dance accompanied by music), and Kayō (vocal pieces). What makes Gagaku particularly fascinating is its fusion of native Japanese compositions with imported musical traditions from China, Korea, and even distant regions like India and Vietnam during the Nara (710-794) and Heian (794-1185) periods. This cultural amalgamation occurred through diplomatic exchanges along the Silk Road, making Gagaku a living museum of East Asian musical history.

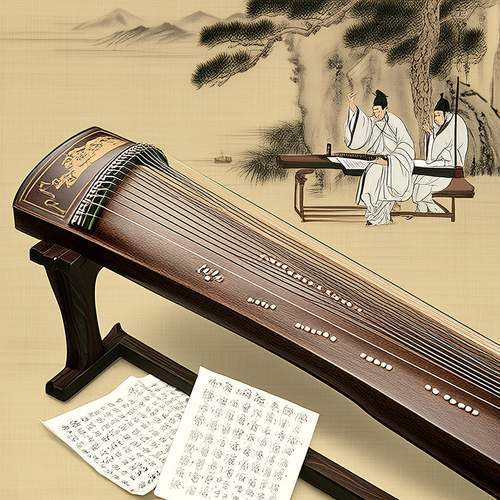

Instruments used in Gagaku create its distinctive otherworldly timbre. The shō, a bamboo mouth organ with 17 pipes, produces haunting cluster chords that mimic the phoenix's cry according to legend. Meanwhile, the hichiriki, a double-reed oboe, carries the melodic line with its piercing yet expressive tone. Percussion instruments like the kakko (small drum) and shōko (bronze gong) mark time with deliberate, spacious rhythms that feel suspended between beats. These sounds combine to create what scholars describe as "organized silence" - a quality that profoundly influenced 20th-century Western composers like John Cage.

The visual dimension of Gagaku proves equally mesmerizing. Bugaku dancers wear elaborate costumes featuring symbolic colors and designs, with some masks and garments preserved from the Heian period. Movements follow strict geometric patterns - circles and squares representing heaven and earth respectively. A single dance might take years to master, as performers train to move with glacial precision, embodying the concept of ma (negative space) through controlled pauses between motions. This creates a hypnotic effect where stillness becomes as expressive as movement.

During the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), Gagaku faced near extinction as Japan rushed to modernize. The imperial court slashed its musical budget, and many musicians lost their positions. Remarkably, the tradition survived through the dedication of a few noble families and shrine priests who continued secret practices. Today, the Music Department of the Imperial Household Agency maintains the official lineage, performing at coronations and state ceremonies while also allowing limited public access through seasonal performances at the Tokyo Imperial Palace.

Contemporary interest in Gagaku has surged beyond preservation circles. Experimental musicians incorporate its instruments into jazz and electronic music, while butoh dancers draw inspiration from its restrained aesthetics. Scholars note how Gagaku's slow tempo and tonal ambiguity resonate with modern mindfulness movements seeking alternatives to frenetic contemporary life. Meanwhile, UNESCO's 2009 designation of Gagaku as an Intangible Cultural Heritage has sparked new academic research into its transnational roots and influence.

For visitors to Japan, several venues offer authentic Gagaku experiences beyond the Imperial Palace. The National Theatre in Tokyo stages regular performances with English explanations, while Kyoto's Heian Shrine hosts spectacular outdoor Bugaku during its autumn festival. Those seeking deeper understanding can view priceless instruments and costumes at the Tokyo National Museum or attend workshops at Tenri University, where musicians teach Gagaku fundamentals to international students.

What makes Gagaku endure as more than a historical relic is its unique temporal quality. Unlike Western classical music that builds toward climactic resolutions, Gagaku unfolds like a slowly rotating jewel, revealing different facets through patient observation. Its very slowness demands - and cultivates - a particular mode of attention increasingly rare in our accelerated world. As cultural historian Tanaka Yūko observes, "To listen to Gagaku is to hear time itself, measured not in minutes but in generations." This living tradition continues to bridge Japan's imperial past with its dynamic present, offering listeners a sonic portal to another dimension of human experience.

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025